Fahrenheit 451 (1966).

As I write this in August 2015, we are in the middle of one of the worst refugee crises in modern Western history. The European response to the carnage beyond its borders is as diverse as the continent itself: as an ironic contrast to the newly built barbed-wire fences protecting the borders of Fortress Europe from Middle Eastern refugees, the British Museum (and probably other museums) are launching projects to “protect antiquities taken from conflict zones” (BBC News 2015). We don’t quite know how the conflict artifacts end up in the custody of the participating museums. It may be that asylum seekers carry such antiquities on their bodies, and place them on the steps of the British Museum as soon as they emerge alive on the British side of the Eurotunnel. But it is more likely that Western heritage institutions, if not playing Indiana Jones in North Africa, Iraq, and Syria, are probably smuggling objects out of war zones and buying looted artifacts from the international gray/black antiquities market to save at least some of them from disappearing in the fortified vaults of wealthy private buyers (Shabi 2015). Apparently, there seems to be some consensus that artifacts, thought to be part of the common cultural heritage of humanity, cannot be left in the hands of those collectives who own/control them, especially if they try to destroy them or sell them off to the highest bidder.

The exact limits of expropriating valuables in the name of humanity are heavily contested. Take, for example, another group of self-appointed protectors of culture, also collecting and safeguarding, in the name of humanity, valuable items circulating in the cultural gray/black markets. For the last decade Russian scientists, amateur librarians, and volunteers have been collecting millions of copyrighted scientific monographs and hundreds of millions of scientific articles in piratical shadow libraries and making them freely available to anyone and everyone, without any charge or limitation whatsoever (Bodó 2014b; Cabanac 2015; Liang 2012). These pirate archivists think that despite being copyrighted and locked behind paywalls, scholarly texts belong to humanity as a whole, and seek to ensure that every single one of us has unlimited and unrestricted access to them.

The support for a freely accessible scholarly knowledge commons takes many different forms. A growing number of academics publish in open access journals, and offer their own scholarship via self-archiving. But as the data suggest (Bodó 2014a), there are also hundreds of thousands of people who use pirate libraries on a regular basis. There are many who participate in courtesy-based academic self-help networks that provide ad hoc access to paywalled scholarly papers (Cabanac 2015).[1] But a few people believe that scholarly knowledge could and should be liberated from proprietary databases, even by force, if that is what it takes. There are probably no more than a few thousand individuals who occasionally donate a few bucks to cover the operating costs of piratical services or share their private digital collections with the world. And the number of pirate librarians, who devote most of their time and energy to operate highly risky illicit services, is probably no more than a few dozen. Many of them are Russian, and many of the biggest pirate libraries were born and/or operate from the Russian segment of the Internet.

The development of a stable pirate library, with an infrastructure that enables the systematic growth and development of a permanent collection, requires an environment where the stakes of access are sufficiently high, and the risks of action are sufficiently low. Russia certainly qualifies in both of these domains. However, these are not the only reasons why so many pirate librarians are Russian. The Russian scholars behind the pirate libraries are familiar with the crippling consequences of not having access to fundamental texts in science, either for political or for purely economic reasons. The Soviet intelligentsia had decades of experience in bypassing censors, creating samizdat content distribution networks to deal with the lack of access to legal distribution channels, and running gray and black markets to survive in a shortage economy (Bodó 2014b). Their skills and attitudes found their way to the next generation, who now runs some of the most influential pirate libraries. In a culture, where the know-how of how to resist information monopolies is part of the collective memory, the Internet becomes the latest in a long series of tools that clandestine information networks use to build alternative publics through the illegal sharing of outlawed texts.

In that sense, the pirate library is a utopian project and something more. Pirate librarians regard their libraries as a legitimate form of resistance against the commercialization of public resources, the (second) enclosure (Boyle 2003) of the public domain. Those handful who decide to publicly defend their actions, speak in the same voice, and tell very similar stories. Aaron Swartz was an American hacker willing to break both laws and locks in his quest for free access. In his 2008 “Guerilla Open Access Manifesto” (Swartz 2008), he forcefully argued for the unilateral liberation of scholarly knowledge from behind paywalls to provide universal access to a common human heritage. A few years later he tried to put his ideas into action by downloading millions of journal articles from the JSTOR database without authorization. Alexandra Elbakyan is a 27-year-old neurotechnology researcher from Kazakhstan and the founder of Sci-hub, a piratical collection of tens of millions of journal articles that provides unauthorized access to paywalled articles to anyone without an institutional subscription. In a letter to the judge presiding over a court case against her and her pirate library, she explained her motives, pointing out the lack of access to journal articles.[2] Elbakyan also believes that the inherent injustices encoded in current system of scholarly publishing, which denies access to everyone who is not willing/able to pay, and simultaneously denies payment to most of the authors (Mars and Medak 2015), are enough reason to disregard the fundamental IP framework that enables those injustices in the first place. Other shadow librarians expand the basic access/injustice arguments into a wider critique of the neoliberal political-economic system that aims to commodify and appropriate everything that is perceived to have value (Fuller 2011; Interview with Dusan Barok 2013; Sollfrank 2013).

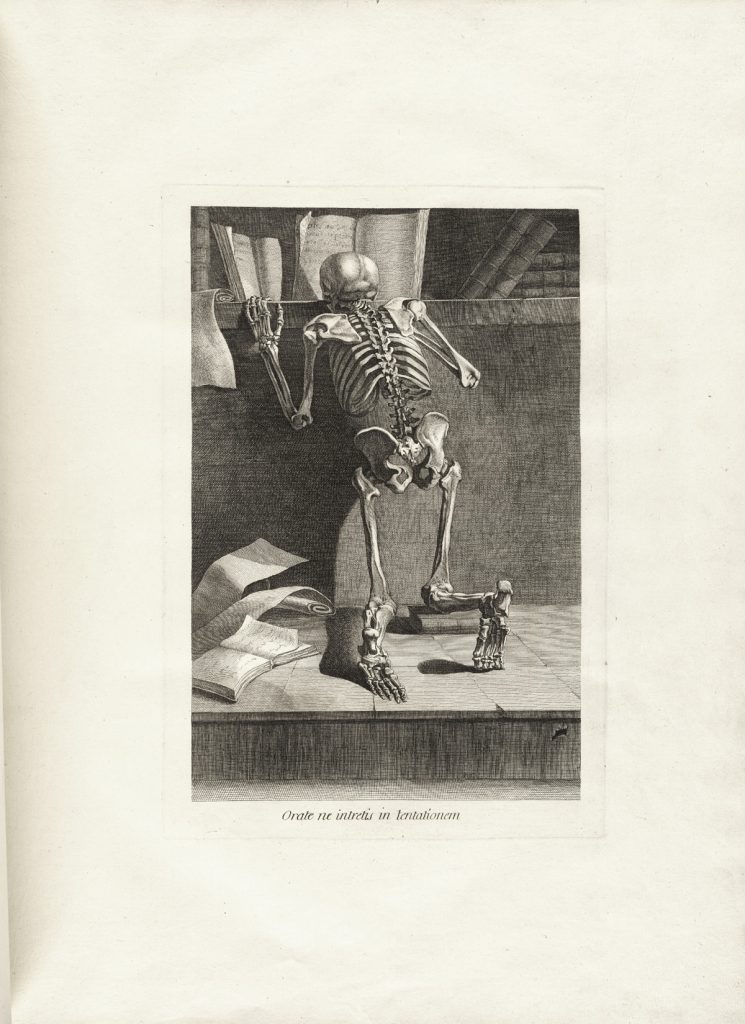

Whatever prompts them to act, pirate librarians firmly believe that the fruits of human thought and scientific research belong to the whole of humanity. Pirates have the opportunity, the motivation, the tools, the know-how, and the courage to create radical techno-social alternatives. So they resist the status quo by collecting and “guarding” scholarly knowledge in libraries that are freely accessible to all.

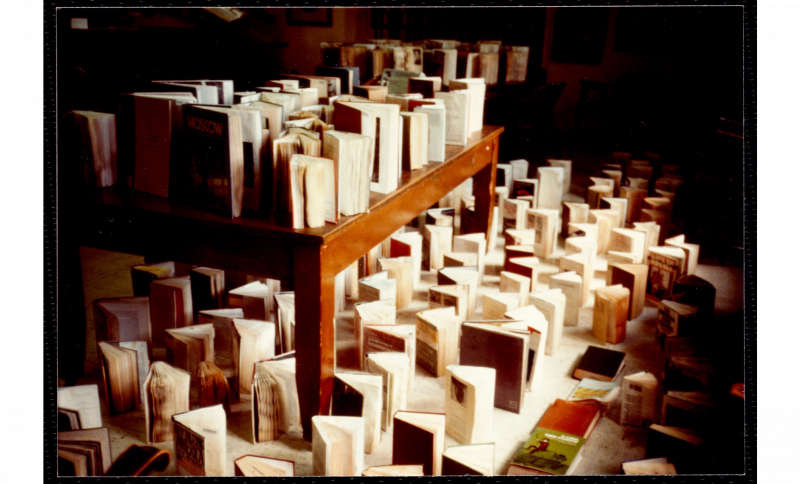

Water-damaged books drying, 1985.

Both the curators of the British Museum and the pirate librarians claim to save the common heritage of humanity, but any similarities end there. Pirate libraries have no buildings or addresses, they have no formal boards or employees, they have no budgets to speak of, and the resources at their disposal are infinitesimal. Unlike the British Museum or libraries from the previous eras, pirate libraries were born out of lack and despair. Their fugitive status prevents them from taking the traditional paths of institutionalization. They are nomadic and distributed by design; they are ad hoc and tactical, pseudonymous and conspiratory, relying on resources reduced to the absolute minimum so they can survive under extremely hostile circumstances.

Traditional collections of knowledge and artifacts, in their repurposed or purpose-built palaces, are both the products and the embodiments of the wealth and power that created them. Pirate libraries don’t have all the symbols of transubstantiated might, the buildings, or all the marble, but as institutions, they are as powerful as their more established counterparts. Unlike the latter, whose claim to power was the fact of ownership and the control over access and interpretation, pirates’ power is rooted in the opposite: in their ability to make ownership irrelevant, access universal, and interpretation democratic.

This is the paradox of the total piratical archive: they collect enormous wealth, but they do not own or control any of it. As an insurance policy against copyright enforcement, they have already given everything away: they release their source code, their databases, and their catalogs; they put up the metadata and the digitalized files on file-sharing networks. They realize that exclusive ownership/control over any aspects of the library could be a point of failure, so in the best traditions of archiving, they make sure everything is duplicated and redundant, and that many of the copies are under completely independent control. If we disregard for a moment the blatantly illegal nature of these collections, this systematic detachment from the concept of ownership and control is the most radical development in the way we think about building and maintaining collections (Bodó 2015).

Because pirate libraries don’t own anything, they have nothing to lose. Pirate librarians, on the other hand, are putting everything they have on the line. Speaking truth to power has a potentially devastating price. Swartz was caught when he broke into an MIT storeroom to download the articles in the JSTOR database.[3] Facing a 35-year prison sentence and $1 million in fines, he committed suicide.[4] By explaining her motives in a recent court filing,[5] Elbakyan admitted responsibility and probably sealed her own legal and financial fate. But her library is probably safe. In the wake of this lawsuit, pirate libraries are busy securing themselves: pirates are shutting down servers whose domain names were confiscated and archiving databases, again and again, spreading the illicit collections through the underground networks while setting up new servers. It may be easy to destroy individual collections, but nothing in history has been able to destroy the idea of the universal library, open for all.

For the better part of that history, the idea was simply impossible. Today it is simply illegal. But in an era when books are everywhere, the total archive is already here. Distributed among millions of hard drives, it already is a de facto common heritage. We are as gods, and might as well get good at it.[6]