It doesn’t take an anthropologist to tell you that your trash is one of the most telling artifacts of your life. For punks, union organizers, private eyes, cops, journalists, phreaks, and hackers willing to get dirty, the dumpster can be a Pandora’s box of treasure, triumph, and tribulation. But what happens when the dumpster goes digital and there’s no garbage man to pick up the trash? Doxing—the act of collecting and publishing information online on a person, organization, or company—has become a controversial tactic to shame, extort, and intimidate targets. Here, I explore how dumpster diving developed as a technique for information retrieval used in court cases, lawsuits, and exposés long before doxing was even possible. What new potential does doxing hold for those seeking more than retaliation or retribution, but rather social justice?

This Is Good Trash!

Throughout my early twenties, my crusty punk friends and I spent hours ripping open bags from grocery stores, retail outlets, and doughnut shops in anxious anticipation of what we might discover. Being piss poor meant dumpstering was the only form of hospitality we could show our visiting friends, who we enthusiastically greeted with bags of smushed crullers and jellies.

Over time it became a way of life for one Boston punk. Knowing how to find good trash earned him a job with the union. He would forage through hotel trash bins looking for information about payroll and employees. Tossing aside soiled linen, empty take-out containers, and tons of pornography, he searched for scraps of paper and small notes. In one find, a manager had thrown away his home phone bill in the business trash. The information was useful to the union, who now knew where he lived as well as who he called. The union staged protests outside the boss’s front door and called every number on the bill to pressure him to negotiate a new contract. Ten years later, this punk turned professional is still scaling fences and doing deep dives for evidence of corporate wrongdoing and to obtain potential leads.

Dumpster diving is a tactic frequently used in other domains, where the found information can be used to compel, extort, or influence others. There is a long history of private eyes digging through trashcans, where investigations involve “wastebasket recovery” of evidence to be used in divorce proceedings and lawsuits. Trash is also valuable to journalists and paparazzi alike, who sort through celebrity rubbish and government bins for evidence of cuddling and/or collusion.[1] While corporations once used dumpstering to gain an advantage over competitors, they have revived this practice to intimidate activists and progressive groups.[2] Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, identity thieves targeted department stores for discarded checks and credit card applications. In these cases, the recovered materials were refashioned as evidence in court cases, sources in newspapers, new commercial products, and to intimidate or impersonate others.

At the same time, phone phreaks and hackers routinely searched dumpsters as a trove of informational treasure. Phreaks were known to crawl through the trash of Bell Telephone and even break into service trucks to obtain lineman’s equipment. While this form of “no-tech hacking” was most popular in the 1980s and 1990s, popular targets included the phone company, high-tech companies, Radio Shack, law firms, banks, and post offices.[3] Crackers and phreaks call this “information diving,” where they seek out not only miscellaneous papers, old faxes, and bills, but also discarded hard drives and other computer waste. Infamous hacker Kevin Mitnick began his career by stealing bus transfers from dumpsters and gaming the transit system. In 2000, Oracle admitted to paying private investigators to go through the trash of Microsoft and their affiliates.[4]

Sneakers (1992)

If info-garbage is really this valuable, why is dumpster diving still legal?

The law here is clear: once an item is thrown away, it is considered abandoned to the public domain. There is one catch, though; if a trash receptacle is on private property, the dumpster diver is trespassing. This law is not in place to protect punks, unions, hackers, or journalists; rather, it serves the police.

In 1984, a Laguna Beach police officer was following leads on a suspect, Billy Greenwood. Failing to obtain a search warrant for his home, local police asked the garbage man to collect his trash and keep it aside for them. In the garbage, the police found drug paraphernalia, which was cause for obtaining a search warrant for Greenwood’s home. Four years later, the California Supreme Court in California v. Greenwood (486 U.S. 35; 1988) ruled that trash is expected to be “readily accessible to animals, children, scavengers, snoops, and other members of the public” and is therefore not protected by the Fourth Amendment. Police departments rely on this precedent to justify sifting through garbage for evidence.

The Dumpster Goes Digital

Knowing where to find good trash is just as important as how to use it. With the Internet, the landfill has changed, and so have the stakes. As more of our lives move online, we now do much of our work and pay our bills on networked computers while also using these same terminals to post images, write screeds, find love, and consume media. If you are anything like me, your hard drive is a garbage can overflowing with discards from the last decade of your life, whereas your Internet history is a digital dumpster that holds untold possibilities for extortion, embarrassment, and the ‘lulz’. Though your physical garbage resides on the curb for a few hours a week, your digital garbage rots for decades strewn across networks, systems, and accounts. Save for the invisible labor of commercial content moderators, who scrub social media platforms of noxious materials, little is done to remove the mundane and everyday detritus of our everyday life online (Roberts 2016).

Hackers (1995)

Doxing involves combing through the digital debris, collecting all pieces of information on that person or group, analyzing how one piece may lead to a new place to look, and then making sense of the information as a single record. Like dumpstering, the method of doxing is similar for the police, union organizers, and private eyes, who seek to build cases against organizations or individuals. For journalists, this kind of digital sleuthing is also a rather routine aspect of the job.[5] Activists tend to take this tactic one step beyond compiling information, publishing the dossier online to shame, embarrass, or bully targets. Websites such as Pastebin or Doxbin are ready-made receptacles for unidentified circulation. Like dumpstering, doxing is a low-tech form of hacking in which information is valuable resource to be exploited.

Doxing is controversial because it has been used to humiliate, shame, and intimidate intended targets. Most notably, “social justice warriors” (i.e., women with opinions and platforms) were doxed by supporters of “ethics in journalism” in the Gamergate scandal.[6] Today doxing is a preferred tactic of right-wing activists, who screenshot videos of leftist protests to identify organizers. Depending on the techniques used to gather information and the level of engagement with the target, doxing can warrant charges such as cyberstalking and harassment, especially if it leads to “real-world” contact such as swatting.[7] Often though, those who do this kind of information diving are not held accountable because the police decline to make arrests or “the doxer” uses methods to remain anonymous (Edwards 2017). Overall, doxing is regarded as a low-cost and low-tech way of intimidating and shaming targets.

Fig. 1: Luckily, I grew up when most people used anonymous screen names, but here is a picture of my cat from 2007 that I recently found when searching an old avatar. Ain’t she cute?

But here’s where the sludge thickens. While doxing can be used to expose, extort, or expel, it can also be a powerful leveler for those who seek social justice when they know criminal justice is far out of reach. Like the union’s use of dumpster diving, doxing holds the potential to pressure institutions to enact sanctions that the courts will not. Doxing has been used by groups such as Anonymous and Occupy protesters in an attempt to expose and reign in police, governments, and corporations.

Doxing of police officers gained mainstream media attention during the Occupy Movement of 2011–2012. Digital information diving was spreading to new groups of activists as a tactic that forced a response. Since 2011, #OpPigRoast continues to be an ongoing Anonymous action in which information about police officers and police unions is collected, archived, and shared.

The doxing of Officer Anthony Bologna was one of the critical factors kickstarting the Occupy movement. A week into the occupation of Zuccotti Park, a NYPD officer pepper-sprayed a small group of protesting women who were already confined behind a police barricade.[8] This video quickly spread through activist networks across the Internet. By looking at different pieces of footage from throughout the day, protesters were able to match the face of the officer with a photo clearly displaying the officer’s face and badge from earlier in the march. The identity-revealing image was tweeted by a labor-activist, who posted the picture to shame the officer who was acting aggressively.

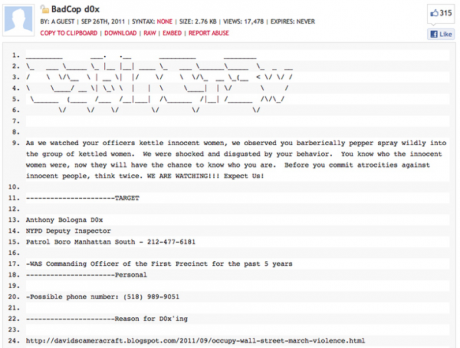

Fig. 2: This is what a dox looks like. For the full dox, see here.

With name and badge number in hand, Anonymous tweeted a dox containing the officer’s name (Anthony Bologna), last known addresses, family members, phone number, and legal troubles. Because Bologna was identified, the story became newsworthy and was subsequently picked up by major media outlets. Bologna’s actions cost the city of New York $382,501 to date and, short of losing his job, he was transferred to a different station.[9]

Lieutenant John Pike, now infamously known as the “pepper-spraying cop,” is another example of doxing for social justice by Occupy protesters.[10] A photo of Pike casually pepper-spraying sitting students at the University of California, Davis, became an overnight Internet sensation.[11] Activists at UC Davis sought to bring Pike to justice by shaming UC Chancellor Linda Katehi; Pike eventually was fired. He was subsequently awarded $38,000 in worker’s compensation for emotional distress after his phone number and email address were repeatedly published online; he reportedly received 17,000 emails, 10,000 texts, hundreds of voicemails, and lots of unwanted mail.[12] UC Davis paid $1 million to victims of Pike’s assault.

More curious though, Pike’s online popularity ended up contributing to former Chancellor Katehi’s resignation. In an attempt to manage UC Davis’s online image, Katehi authorized $175,000 in university funds to scrub the Internet of references to this event and to improve the school’s reputation. Protesters continued to pressure Katehi long after the Pike incident, while journalists and administrators investigated her contracts, affiliations, and conflicts of interest. Allegations that she tried to polish her own online image using university funds led to her undoing.[13]

While reputation management firms sell products they claim can improve tarnished reputations, currently there is no way to tell shit from Shinola. More than just rebranding UC Davis, aides reported that Katehi simply wanted them to “get me off the Google.”[14] Reputation management firms know all too well that there is no surefire way to remove information from the Internet. Instead, they fill the bin higher and deeper with more junk, hoping to cover over what’s at the bottom, like a cat in a litterbox.

Importantly, the information obtained and published about these officers was already public; it was just a matter of knowing where to look for information, where to publish it, and ultimately how to use new and old media to unlock its potential. Poking around at the fetid leftovers online seems to be fine as long as you do not try to leverage that information politically. Whereas the police have found it advantageous to ensure they have access to curbside rubbish, these online scraps are legally ambiguous for civilian doxing.

This Place Is Starting to Smell

What was once a specialized tactic of punks, journalists, unions, police, phreaks, hackers, and private detectives, dumpster diving has proliferated for all types of reasons. We used to rely on the telephone book to share public information; today, things like phone numbers and home addresses should be preciously protected information in an era of digital dumpsters. What’s most concerning is that information abandoned online is more durable than the stuff we throw into those enormous steel bins. Because the Internet is designed to capture and distribute information to the widest audience, once information is posted, it is difficult to erase. The tools of search, hyperlinks, screenshots, and the ease of copy/paste supports the proliferation of content, not its disposal. Just like trashcans, the digital dumpster has overflows. For Katehi, this was an expensive lesson.

Activists know that doxing is an effective tactic when applied to pressure sanctions from civil institutions. Occupy protesters used the information networking capacity of the Internet to bring together stores of information into a single container and repackage it for popular consumption. So far, no one has been charged with publishing or sharing information about Bologna or Pike. For Occupy protesters, doxing was a demand for social, not criminal, justice. In doing so, we see that when the dumpster goes digital, movements can expand their political capacity by sorting the good trash from the bad, giving new meaning to the call to refuse and resist!