“Where does the boundary lie between the history of knowledge and the history of imagination?” (Foucault 1991: 64). Or, what is a systemic risk?

Background: The Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) enacted into law in 2002 established a formula whereby the private insurance industry and the federal government would share insurable losses in the event of a terrorist attack in the US. Originally enacted for a three-year duration, with explicit recognition of its anticipated temporary status, the Act was extended in 2005 for a further 2 years and again in 2007 for a further seven-year period. The original stated rationales for the Act were:

- By limiting the potential losses of insurers, the provision of private terrorism risk insurance would be encouraged.

- A period of federal financial support would provide the insurance industry with an intervening period of time to acquire more knowledge about the insurability of terrorism attacks and develop the statistical tools and actuarial methods to facilitate the private insurance process.

A detailed and accessible summary of the legislation is available here

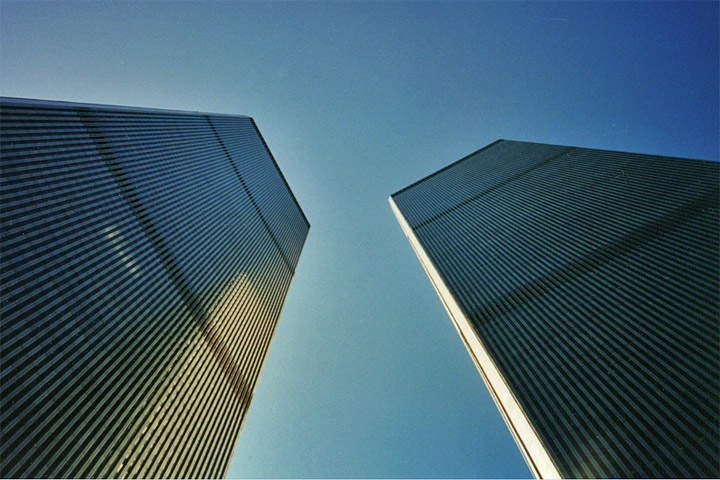

After 9/11, insurance companies, insureds and legislators imagined the risks posed to the future functioning of the national economy by recent events and by the possibility of further terrorist attacks. The specter of a possible systemic risk to the economy was raised. Insurers and reinsurers chastened by their approximate $40 billion compensation payments for 9/11 property damage imagined that “it will be impossible to provide our customers with terrorism coverage” (US House, September 26, 2001, 39).[i] Insureds either in the form of organizations representing real estate and construction industries,[ii] or owning property considered particularly susceptible to attack, ‘trophy targets’[iii], imagined the financial consequences of their particular vulnerability to the unavailability of terrorism risk insurance. Legislators imagined the risks to the economy if corporations were unable to insure assets against damages from terrorist attacks: insurance is “the glue which holds our economy together” (Congressional Record, November 29, 2001, H8573).

Had a systemic risk to the US economy emerged: one perhaps consistent with Beck’s (1992, 1999, 2002) risk society thesis that without federal financial support, insurers could not and would not want to insure terrorism risk? Nobody knew for certain: imagined realities were to the forefront. Beck attributed uninsurability to the delocalized, incalculable and non-compensable elements of the danger. Delocalized refers to the uncontained effects of misfortune whereby unfavorable consequences ‘spill over’ into other physical and temporal zones and outside of insurance parameters. Incalculable refers to a resistance to quantitative assessment rendering risk metrics and actuarial calculations as hypothetical. Non-compensable refers to destruction of such magnitude that monetary restitution no longer proves sufficient. Each of these three suspected impediments to insurability was extensively discussed in legislative hearings. Proponents of TRIA and federal financial support emphasized the plausibility of the impediments while opponents queried their status of intractability as barriers to insurability.

This observation provides a means of thinking about the idea of the becoming insurable of terrorism risk. The Deleuzian concept of becoming suggests the moving, underdetermined and unfinished process of the insuring of terrorism risk. Becoming also resonates with Foucault’s disquiet with strict epistemological demarcations. Becoming is the in-between: for us the boundaries of insurability and non-insurability. An imaginary of the insurability of terrorism: its necessity, feasibility and sustainability. Also an imaginary of non-insurability: its excess, infeasibility and fragility. The becoming insurable of terrorism risk, in particular the role federal funding might play, passed in-between these imaginaries. In doing so, all types of terrorism risk insurance boundaries were explored: the boundaries between risk and uncertainty, between the calculable and non-calculable and between private opportunities and public responsibilities. In slightly different terms, boundaries were explored by imagining the possible systemic risk the unavailability of terrorism risk insurance might pose to the economy and how it might become insurable.

Whilst imagined and often precariously drawn, such boundaries should not be considered as inconsequential: boundaries “transmit and control exchanges between territories” (Richter and Peitgen 1985: 571-572). Present and future financial relationships between the public as taxpayers, corporations, insurers and reinsurers were shaped by these boundaries: who would provide monies, to whom, when and in what amount in the event of a future attack. What might be considered the financial engineering of systemic risk. An engineering, however, susceptible to continuous re-engineering as different imaginaries of terrorism risk were re-imagined.

Two further observations are relevant. Firstly, the identification of terrorism risk insurance as an issue of economic wellbeing did not fortuitously appear on the legislative agenda: proponents and sponsors with different interests and agendas aligned to promote insurance as a necessary and legitimate legislative concern. Shifting imaginaries of ubiquitous yet ethereal danger marked this terrain. Secondly, possible future terrorism risk insurance arrangements required exploration, formulation and evaluation: an exercise consisting of the imaginative alignments of moving contingent financial relationships. Stated succinctly: imaginaries were employed to construct various scenarios of whether a systemic risk to the functioning of the US economy had emerged.

Some Boundaries and Imaginaries in the Becoming Insurable of Terrorism Risk:

A boundary between the indispensable and dispensable status of insurance:

Insurance is “critically important not just to insurance companies, agents and brokers, but also to the future viability of literally hundreds of thousands of small and large US businesses” (Statement of the Independent Insurance Agents of America, US House, October 24, 2001: 169).

Proponents of TRIA “speak out of the opposite sides of their mouths… the same people will argue that the creation of a natural catastrophe fund is simply a bailout, that it will supplant the private market, or that taxpayers will be subsidizing high-risk areas” (Representative Brown-Waite from hurricane prone Florida proposing a federal fund similar to TRIA in the event of natural catastrophes, 2007).

A boundary between public responsibility and private opportunity:

“Clearly this is just not an insurance issue. This is an issue that will affect our entire economy” (Representative Oxley, Chairman of the House Committee on Financial Services, US House, October 24, 2001: 3). (link)

“the insurance companies see this as an opportunity. A number of records sent back and forth…. have made it clear the time is now to fully exploit the opportunity that was presented by September 11 in terms of creating new companies, creating new entities, and going after capital” (Representative Miller, California, Congressional Record, November29, 2001: 23329)

A boundary between non-calculability and calculability:

“Let me begin by stating some very simple facts… We do not know where it is going to occur. We do not know when it is going to occur. We do not know how often it is going to occur. And we do not know how much it is going to cost when it does occur”. (Csiszer, President and CEO, Property Casualty Insurers of America, US House, July 27, 2005: 54).

The insurance industry “can predict, not with precision, because this is not a precise thing… but you can predict… it is doable and is being done (Hunter, Director of Insurance Consumer Federation of America, Senate, May 18, 2004: 69, a vociferous critic of the necessity of TRIA). (link)

A boundary between risk sharing and private choices:

“Whether the market can or cannot do this is not to me the primary concern”, the risk “ought to be broadly shared. This is a case for totally socializing the risk” (Representative Frank, Massachusetts, US House, July 27, 2005: pp. 5-6). (link)

The case against risk sharing: “I have farmers in my district, they have chicken houses… Those farmers do not feel like those chicken houses and those chickens need insurance against terrorism” (Representative Bachus, Alabama, Congressional Record, US House, November 29. 2001, H8617). (link).

Postscript on systemic risk and becoming insurable: “What is real is the becoming itself… not the supposedly fixed terms through which that which becomes passes” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987: 238): points to the problematic status of assessing whether a risk is systemic and its insurability.