The Participatory Development Toolkit is a “small briefcase (26 x 33 x 10 cm) containing 221 activity cards, 65 pictures, 11 charts, 1 guidebook”; it is “covered in brown pattered cloth, with leather handle and leather snap closure.” It is decorated with drawings of women, abstract patterns, huts, trees, animals: drawings, the kit’s guide explains, “by the Warli tribe, who live in the Sahadri mountains in Maharashtra state north of Bombay” and who are “known for their mythic vision of Mother Earth, their traditional agricultural methods, and their lack of caste differentiation” (Narayan-Parker and Srinivasan 1994).

The Participatory Development Toolkit, created by Deepa Narayan, Lyra Srinivasan and others, funded by the World Bank and the United Nations Develop- ment Program, produced in India by Whisper Design of New Delhi, coordinated by Sunita Chakravarty of the Regional Water and Sanitation Group in New Delhi in 1994. This copy owned by the Getty Research Library, Los Angeles, CA.

The Participatory Development Toolkit was created in 1994 primarily by Lyra Srinivasan and Deepa Narayan, two development professionals who at the time worked for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the World Bank. Unsnapped and opened, it reveals a set of 25 folders and a booklet: “Each individual envelope is coded with a number and a title on its flap.” The lid folds back to allow the kit to form a stand, and “every fifth envelope has a color-coded tab. To gain access to the materials in each set of envelopes, pull the tab and the envelopes will extend toward you” (Narayan-Parker and Srinivasan 1994). The Participatory Development Toolkit arrived at the zenith of the rage for “participatory” development. That enthusiasm lasted from the early 1970s, when the United Nations created a “Popular Participation Program” (Pearse and Stiefel 1979), to the 1980s spread of “participatory action research” (Reason 2008), to the prominence in the 1990s of the “participatory rural appraisal” (Chambers 1994) to the 2000/2001 World Bank Development Report, which incorporated “Participatory Poverty Assessments” from around the world (Green 2014; World Bank 2001). Alongside the World Bank Development Sourcebook (World Bank 1996) and a range of other handbooks and sourcebooks and kits, the Participatory Development Toolkit stands out for being an actual kit: a briefcase containing folders that reveal a range of activities, cards, photographs, game pieces, puppets (“flexi-flans”), and, especially, sets of images.

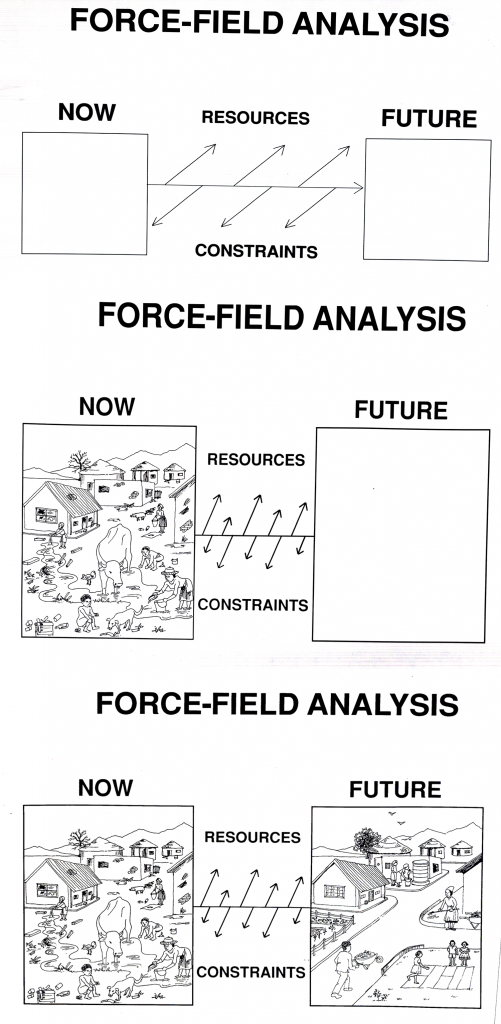

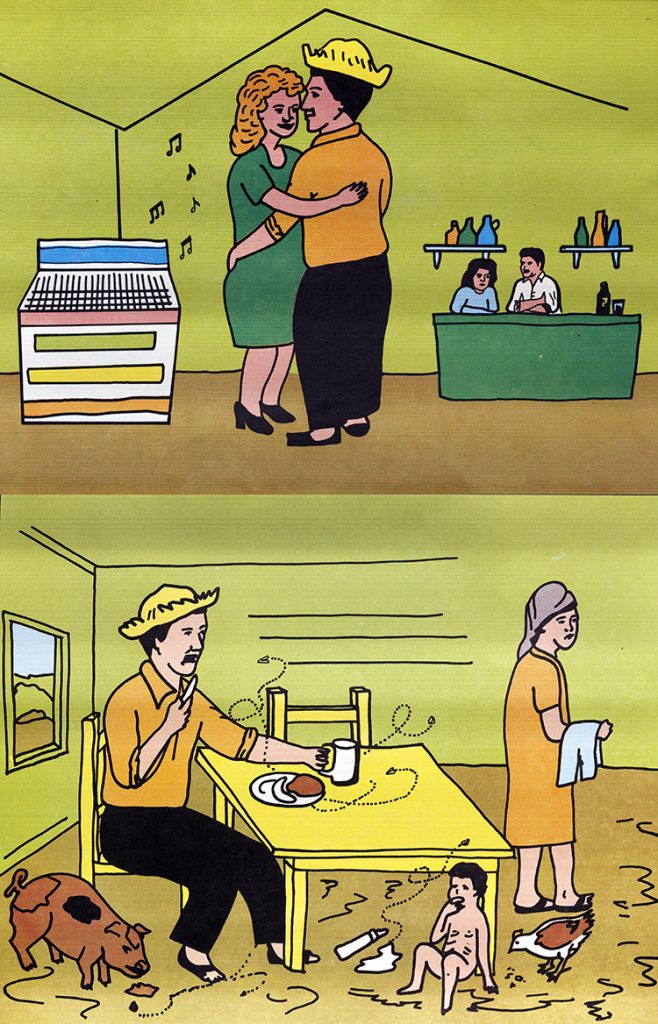

One can sense in the Participatory Development Toolkit an enthusiasm for inclusiveness, respect, curiosity, and a close-to-the-community style of development; these games, cards, and images are designed to draw people into discussing problems and situations that immediately affect them, to elicit stories and images of the future they would prefer to have, and to debate the solutions to the problems they experience. There are countless versions of a sort of now-and-later game: pictures of unsanitary, impoverished, violent nows, followed by cleaner, wealthier, more humane laters.

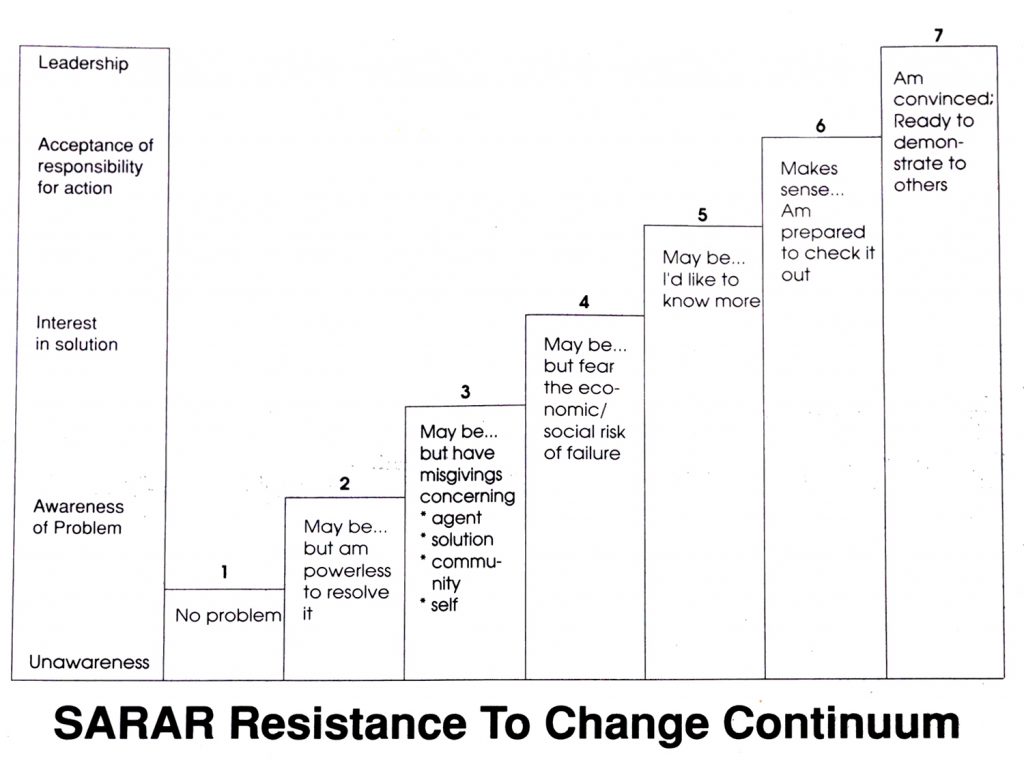

It’s not clear how often the kit (itself) was used. The games and images and techniques it contains show up in different settings across decades of attempts to install participatory development in various times and places. Many of the 25 different folders contain activities from Lyra Srinivasan’s SARAR[1] methodology, one of dozens of different packaged methods for engaging people in participation and collective uplift. Others are cribbed directly from the social psychology of Kurt Lewin, who himself inspired a generation of “participatory” research, especially in management (Alden 2012; Lezaun and Calvillo 2014).

But the simple fact that the kit exists at all is worth dwelling upon. Why was a “toolkit” necessary for an activity called “participatory development” in the 1990s? Who were the tool users, and what might they have done with it? Is the toolkit a device for enticing participation, for improving it, or for something else? What imagination drove its form and function, and can we learn anything from it about today’s attempts to build little development devices, or design humanitarian goods? Can we think of the Participatory Development Toolkit as a precursor to our contemporary attempts to transform development through apps, platforms, algorithms or infrastructures?

The Problem of a Participatory Development Toolkit

At the heart of this kit is a conundrum. The toolkit seeks to “scale up” and spread globally something conceived of as essentially “context specific.” Participatory development, in most of its different guises, has always resisted the idea of a uniform, universal, top-down, one-size-fits-all development. Along with many other critiques of such dreams, participatory development proposes that proper development success should depend on attending to the very specific needs of particular people. Each community, village, neighborhood, council, or agricultural extension district is its own special place, with its own special needs that cannot be simply treated just like the next. Rather, development should involve the residents in diagnosing problems and planning solutions.

A toolkit is a device for decontextualizing: it is filled with tools that can be used in multiple different contexts, tools that are standardized and hardened into a semi-universal state. But the tools are not automatic; a toolkit implies the existence of a skilled tool user as well. A toolkit sits somewhere between an imagination of a context-specific, autonomous, and self-guided development without any facilitation on the one hand; and on the other, the large-scale, universal, automatic spread of one-size-fits-all solutions everywhere. The Participatory Development Toolkit itself reflects exquisite awareness of this problem. The authors take pains to mount warnings at every turn: the kit does not stand alone; the images and games should not be used without adapting them; the kit should not be used to extract information (rather than incite participation); the user of the kit should be prepared to give up control of the kit; the kit, indeed, is not essential (see, for example, Narayan-Parker and Srinivasan 1994:1–5; Srinivasan 1990:12–13).

In between universalism and hyper-specificity sits the kit: mediating by taking what works at a local level, attempting to quasi-formalize it, and inserting it into a briefcase so that it can be carried to the next site to repeat its context-specific success.

“Scalability” of this sort is also at the heart of our contemporary enthusiasm for apps, platforms, and quasi-algorithmic solutions to the problems of developments. The large-scale “big development” projects of mid-century, where scale often meant simply “large,” used “economies of scale” to attain a certain economization or efficiency as a project grew larger; conversely, the “small-is-beautiful” technology solutions of the 1970s counseled a return to the local, the situated, and the appropriate. But contemporary scalability sees in the small a mere instance of the large: a solution at the small scale (e.g., a LifeStraw for dirty water; Redfield 2016) can be “scaled up” and distributed globally. It is small and large at the same time. Some kinds of “tools” are scalable in this sense (software and algorithms preeminent among them), and others, perhaps, are not (dams and bush pumps).

The Participatory Development Toolkit tries to accomplish something similar: it takes a program for participation developed in response to specific cases, generalizes it, and spreads it to other sites and cases. It is “quasi-algorithmic” in the sense that it involves a set of steps in a sort of recipe, but it also relies on the existence of both a skilled tool user (the facilitator of participation, usually a development professional of some kind) and a defined group of participants (women, members of a village, a congress of delegates, extension workers, etc.). Such collectives are called into being just at the moment when the kit is in use. This process produces an experience called “participation.”

To put this contemporary problem in perspective, it is important to emphasize that there have over the decades been plenty of examples of “experiments with participation” not only in development, but also in art, in science and technology policy, in urban planning, or in the workplace (Kelty 2017; Lezaun et al. 2016). It is worth turning to the history of participatory development to understand better what these past experiments sought to achieve.

The Participation That Was

Participatory development has failed at least once already. This is perhaps not obvious to a generation of development workers or scholars discovering participation for the first time in the 2010s. In the 1970s both small, alternative groups (such as Budd Hall and the Participatory Development Network) and large organizations such as the United Nations Popular Participation Program embraced an earlier version of participatory development with enthusiasm. And as it succeeded from the 1970s to the 1990s, it came in for its own critique: by the year 2001, participatory development was being called “a new tyranny” (Cooke and Kothari 2001). The book bearing that subtitle suggested that many things had gone wrong with participation: that it had been bureaucratically routinized; that recipients were gaming the system to become “professional participants”; that it rested on a myth of community or village structure that was inadequate in most places, or to the realities of globalization, and so on. Perhaps most important, it wasn’t clear that participatory development alleviated poverty any better than non-participatory development had.

There was also a clear sense, captured best in Francis Cleaver’s critique, that true participation had been betrayed by toolkits in general:

“Participation” in development activities has been translated into a managerial exercise based on “toolboxes” of procedures and techniques. It has been turned away from its radical roots: we now talk of problem solving through participation rather than problematization, critical engagement and class (Cooke and Kothari 2001:53).

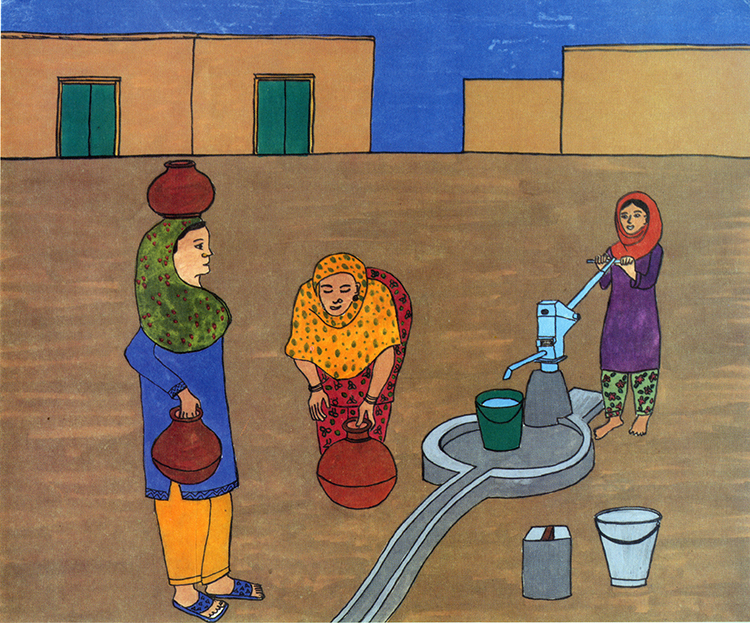

Unserialized Posters; from “Fourteen pictures showing various human situations and interactions.” Activity #7 in (Narayan-Parker and Srinivasan 1994, pp. 20-21)

What were these radical roots, and how did they grow into a Participatory Development Toolkit? There are multiple interesting origin points for the Participatory Development Toolkit. The “radical” that Cleaver is no doubt thinking of is the work of Paolo Freire and more generally of “participatory action research” from the early 1970s onward (Freire 2014; Reason and Bradbury 2001). The idea that toolkit makers might try to roll up Paolo Freire and tuck him inside a kit is perhaps surprising, but actually quite obvious if one reads his work carefully. Freire’s ideas of “conscientização” dictated not just a participatory engagement with the impoverished subject, but in particular the use of imagery, games, and specific forms of contextualization. The instructions for using these images in the Participatory Development Toolkit parallel Freire’s own discussion of them in Pedagogy of the Oppressed (2014): they must be “non-directive” (i.e., not “sectarian”) and they must rely entirely on the perceptions (and “perceptions of previous perceptions”) of the “wretched of the earth” themselves. Many of the activities of the kit are directed toward instilling first an understanding of this “non-directive” form of analytical work, to be followed only later by substantive discussion of pumps, latrines, disease, and so on. Once inside the kit, however, Freire’s radical, Marxist pedagogy runs the risk of appearing lightweight and inauthentic, transformed into an exercise in “project management” ripe for critique.

Stuffed inside the kit alongside Freire is Robert Chambers, the development scholar and practitioner most often associated with the rise of participatory development in the 1980s. Chambers started life as a colonial administrator in Kenya, and it was only late in the 1980s that he began to embrace participation as a technique (Cornwall and Scoones 2011). He came to it not as Freire did, as a liberation of the wretched of the earth, but primarily as a question of ascetic practice, which is to say it was less about the participation of the impoverished villager than a form of work on the self for the development professional. Chambers was primarily concerned with “seeing reality” clearly in the hopes of transforming poverty, and he insisted that most of what development professionals did obscured reality: they engaged in “rural development tourism,” they suffered from “tarmac blindness” and “survey slavery” (Chambers 1983). They needed to be given the tools to see what was right in front of them, and to this end, Chambers advocated the flexible use of multiple different methods.

To address this problem, Chambers pioneered a kind of “method of any method,” by which development workers could transform the simplest of techniques, like walking around and talking with people, into legitimate tools in a toolkit. Interviews, transect walks, pocket charts, ethnographic observation, and much more were lumped together and labeled “participatory rural appraisal.” The approach is clear in the Participatory Development Toolkit: there are 25 folders with different games and activities, each appropriate to a different challenge. There are also explicit directions, much like those that Chambers issued in everything he wrote, to “improvise” and adjust activities to the context and the site in question, to extend the kit and add to it, and, especially, to do so with the participation of those at the receiving end of development’s interventions.

Chambers’ approach implied that any such toolkit required a skilled tool user, and to become such a person, one had to work on oneself, develop new capacities, overcome blindness, see reality clearly, and so on. Only such transformed development workers would be able to effectively take this kit to the field to elicit the kind of participation promised by the likes of Freire (whom he recognized but did not claim as an inspiration). Despite the step-by-step nature of the toolkit (or any of the sourcebooks, scripts, or manuals promulgated as “participatory development”), the quasi-algorithm required a bit of human input: not just any human input, but that of self-reflective, awakened experts.

From the perspective of a later critic such as Cleaver, the toolkit is a proxy for the rigid, hierarchical, male engineer who sees a standard, technological solution to every problem. Participatory development—radical or not—is directly opposed to such powerful, unaccountable forms of decision-making. To the extent that the figure of the Engineer is the tool user, the toolkit is dangerous.

From Chambers’ perspective, however, the enlightened user of the toolkit can achieve a different outcome; tools are figured as neutral and emancipating when given to the right people by the right people, and the result would be the scalable development of both the professional agent and the impoverished subject of development.

Device, Toolkit, Algorithm

What is at stake in thinking of the Participatory Development Tookit as a “quasi-algorithm”? What might be the difference between a briefcase of paper games and routines for eliciting participation, and a piece of software that tries to do something similar, but is implemented on a solar-powered, GPS-enabled, data-intensive smartphone app? Can we see this kit as a vantage point from which to evaluate the contemporary explosion of various devices for development, especially those that demand the input of users concerning local conditions while using standard forms and algorithmic procedures to scale up and travel?

One obvious thing to say about the Participatory Development Toolkit is that it does not contain tools or supplies of a conventional kind. There are no hammers, pliers, or wrenches; there are no Band-Aids, gauze, or Bactine as there would be in a first aid kit; it is not quite the “kit” pioneered by Médecins Sans Frontières capable of unfolding an emergency treatment center in a remote or decimated location (Redfield 2013:69ff). Instead, it contains scripts, games, and procedures designed to elicit experiences. When opened and set into operation, it tries to create a joyful occurrence: people are called to draw pictures, make maps, play a game, or discuss a problem related to their immediate life experience and surroundings. In this respect, its “devices” are similar to what Soneryd and Lezaun call “technologies of elicitation,” or what Caroline Lee refers to as “do-it-yourself” or “designer” democracy; they are procedures and practices of convoking individuals to elicit debate, deliberation, opinion, or decision-making (Lee 2014; Lezaun and Soneryd 2007).

The toolkit is not, however, immaterial as a result. The material properties of the Participatory Development Toolkit are important; it is meant to travel, it has a handle, and it carries both its theory and its practice in easily accessible compartments and a handy users’ manual. The toolkit is not a device itself, but more like a “platform”: a box full of different devices all dependent on a similar form of action and general theory of participation. These devices are not technologically sophisticated, but neither, really, are most apps or software programs. They may depend on a technologically sophisticated infrastructure (to exist), but at the end of the day they are simple programs: devices designed to achieve particular results. What is the relation between the participating humans and the toolkit? In the toolkit, the games and images and scripts call on people to interact in specific ways. The development agents, along with those they interact with (villagers, women, engineers, farmers, politicians), are given rules, or shown images, or follow loose scripts for “non-directive” interaction with each other. The goal, or outcome, is to either diagnose a problem or propose solutions to it. It does not solve a problem diagnosed elsewhere, higher up or far away, without the involvement of people, but presumes instead that the diagnoses of a problem itself has yet to happen, or that the proposed solutions must come from the context-specific encounter itself.

This is the origin of its power: it promises a highly context-dependent exploration of problems specific to those who meet and engage in the production of these experiences. This is why it enrolls people into its project. The conundrum comes from the fact that the devices for eliciting such experiences are (perhaps unwillingly) universalized in the toolkit, made to travel. Whereas an individual development consultant might bring a set of techniques and procedures with her to a variety of (necessarily limited) places, the Participatory Development Toolkit implicitly suggests that through replication, many more people can carry these procedures to many more places.

What’s more, it is not merely a toolkit-as-commodity being replicated; it is also a toolkit funded by and branded with the insignia of the World Bank and the UNDP. These institutions make participation more or less bureaucratic, and authorize them as forms of practice. It is not clear that the Participatory Development Toolkit was required in any way, but along with manuals such as the World Bank Participation Sourcebook (World Bank 1996) the techniques and procedures were incorporated into the standardized practices of development. One can find the same games and scripts in the Sourcebook that appear in the Participatory Development Toolkit.

The institutional standardization of participation is what provokes the suspicion of the toolkit itself, in cases such as Francis Cleaver’s critique above; rather than a highly contextualized participatory engagement, it suggests instead a bureaucratically standardized set of forms and practices, riven from the context. Soneryd makes a similar point in discussing more recent “technologies of participation”: it is not an accident that this standardization happens precisely because many actors in these organizations actively seek to “imitate and replicate” forms of participation that have worked elsewhere (Soneryd 2016:149).

Such institutional embedding (to use the new institutionalist language) is not dissimilar to the kind of infrastructural “network effects” (to use the engineering/economic language) of internet-based apps and platforms that similarly circulate plans, techniques, and procedures in the interest of producing an experience. As the kit succeeds, it draws more people into a particular form of participation, and produces professionals and networks of practice that draw on these tools as exemplary forms of participation. Both aim at scaling up and circulating the local without losing (the character of that) local specificity. But such tools are inevitably subject to both technological and institutional mimcry, standardization, and control, whether that be an audit culture of measuring results or an advertising-dependent system of revenue generation.

The Participatory Development Toolkit represents a stage in this evolution. It is “quasi-algorithmic” but not fully routine in the sense that it does not operate automatically, in the absence of context, judgment, or serendipity. Nor is it “computational” in any sense. Rather, a development agent takes the place of the networked computer: he or she runs the program (as a neutral agent: a CPU, as it were) and records the data into memory. The users of the algorithm are the participants: villagers, women, extension agents, etc. They give their data and ideas to the machine in the hopes that it will spit out a solution and perhaps some money.

The term “algorithm” used to mean a set of rules, not unlike a recipe, or the rules of a game. In this respect, the operator is like a player or a chef: some are good and some are bad. Robert Chambers’ desire to see development agents remake themselves as agents of participation relies on such a notion: you can have the best recipes in the world, and still produce a bad meal.

Lately, however, the “algorithm” has come to mean something more than just a set of steps. Rather, it is a kind of living system that depends both on computational processing of recipe-like rules, and on the constant input of many participants: participants who feed it regularly, not just use it. The Facebook timeline, to take only the most storied case, depends both on a large set of rules of searching, sorting, and comparing possible content, and on an always-changing database of what people who are connected to other people view, like, linger upon, or swipe past. This is not the same thing as a simple set of rules that depend on expert execution; rather, it seems to enable a certain fantasy of—and provoke a certain desire for—participating in an enormous, amorphous, yet nevertheless intimate collective that represents itself to itself constantly.

In its ideal version, this happens completely without human control or intervention, making the local into a universal. In reality, such “automation” reproduces the good and the bad of the local (as Facebook, Twitter, and others are discovering in the case of the 2016 U.S. election), and a reversion to the former meaning of algorithm becomes more appealing again.

Seen from this perspective, the Participatory Development Toolkit is an interesting moment in the development of devices for development. It is perhaps more like the algorithm-as-recipe in its quaint leather-bound form, but perhaps it also betrays a desire for the newer algorithm-as-system in which all over the world, people are enabled to participate constantly in the diagnosis and solution of their own problems. Or maybe it should be seen from the success of the contemporary demand for constant, unreflective participation of the sort promoted by social media. Perhaps it reveals a now nearly forgotten desire for scaling up something difficult to scale up: the reflexive practitioner whose “algorithm” is human judgment, memory, and discernment, and not an automatic, machine-learning, artificial intelligence. Perhaps it reveals a present danger of an endless participation without deliberation, whereas the analog briefcase could still, at least, contain a trace of the reflexive practitioner, the Marxist pedagogue, or the evangelical development aesthete.