The mobile phone revolution in Papua New Guinea (PNG) began in July 2007 when Irish billionaire Denis O’Brien’s company Digicel, in response to the government’s liberalization of the tele-communications sector, began rolling out its wireless network. Digicel was warmly welcomed by a country whose citizens felt neglected—if not downright mistreated—by the erstwhile state-owned monopoly Telikom due to the prohibitively expensive and geographically limited wireless services of its subsidiary Bemobile. Digicel did not disavow nationalism, to which Telikom reactively appealed, and also apparently cared about PNG, sponsoring sports teams and cultural festivals.

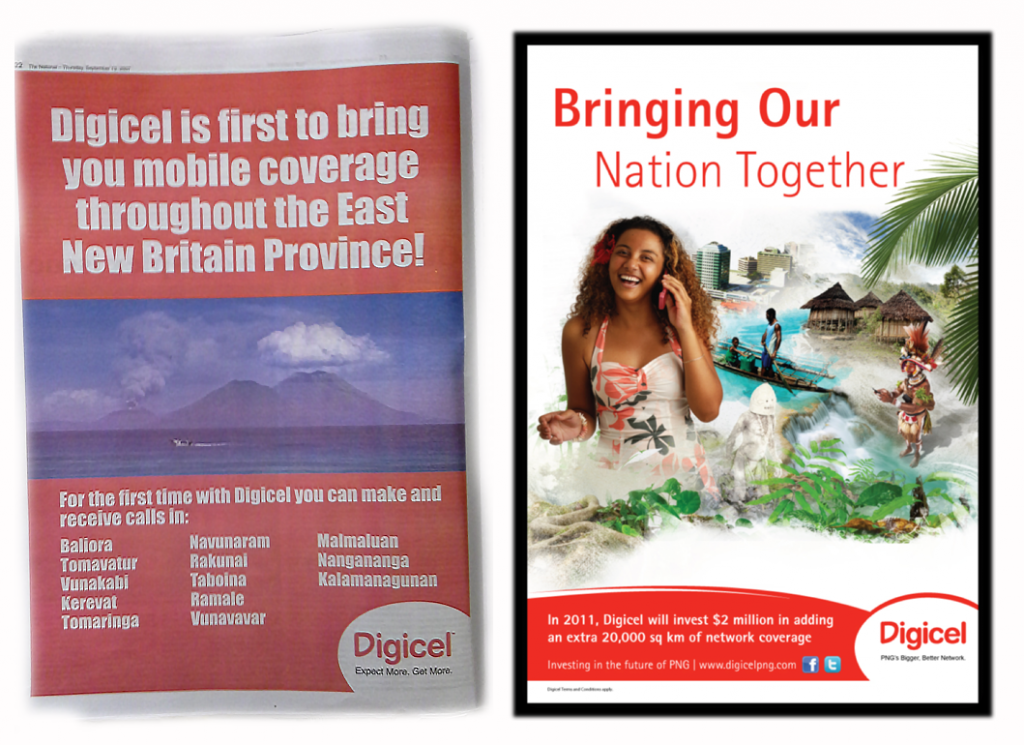

Most important, Digicel delivered wireless service to areas where it was never before available (Fig. 1), thus making good on its promise to bring the nation together (Fig. 2).

Individual customer benefits mattered too. Digicel quickly put basic handsets such as the Nokia 1020 within affordable reach of tens of thousands of people, many living in remote rural areas. By virtue of small, prepaid purchases of airtime, villagers could for the first time experience long-distance communication, especially with kin living and working in urban centers. And when a customer had no credit on her phone, she could use the free “call me” short-message service (SMS) to request that a loved one get in touch (Fig. 3). Digicel clearly understood the value of mobile phones as affective technologies, objects that “mediate the expression, display, experience and communication of feelings and emotions” (Lasen 2004:1).

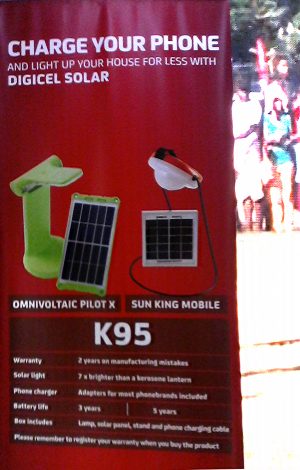

Fig. 1. (left) Digicel newspaper ad, September 2007. Photo by R. Foster

Fig. 2. (right) Digicel ad, circa 2011.

❧

In the beginning, people did not have many numbers to call or much credit with which to call. So they called Customer Care. Dial 123. 24/7. Free. They still call. But now there is a charge for calling during off-peak hours. The charge is meant to discourage prank calls, especially late at night.

People also called numbers randomly in search of phone friends who might become romantically involved and eventually meet face to face. Persistent calls from unknown numbers became a common topic of public conversation and a compelling justification for legislating mandatory registration of subscriber identity modules (SIM cards), which finally happened in 2016.

Mobile phones entrained new possibilities not only for sustaining long-distance kin relations but also for experimenting with self-development. The capacity to engage in novel forms of intimacy with strangers and in private forms of communications with intimates was welcomed by some, decried by others, and regarded with ambivalence by most people. New ways to express care and concern—such as sending and receiving credit requests for airtime—were offered by a company that promoted itself as a caregiver to its customers and to the nation as a whole.

At the same time, mobile phones, understood as social and material assemblages that include more than the discrete handset, were taken up in ways that exposed the premises of a robust moral economy: what companies, consumers and state agents owed to each other posed a perpetually open question. The capacity of the PNG state to regulate Digicel, which owns and controls the network it built, is weak; the business challenge faced by Digicel to overcome the absence of a reliable electric power grid and the chronic insecurity of corporate assets such as cell towers, which are regularly vandalized, is enormous; and the ability of consumers to use the network in the face of limited financial means and increasing demand for smartphones and data is always under threat.

In short, the moral economy of customer care in PNG is precarious for everyone. Here I offer five brief ethnographic examples.

❧

Karen acquired her first mobile phone when she came to university in the capital city of Port Moresby in 2011. She already had friends who owned mobile phones despite an official ban on the devices at her high school. But at university, every student seemed to have not just a phone, but a smartphone that enabled use of the internet for their studies. Having a phone appeared to be a standard expectation, and students who did not have them felt an acute sense of being left out. Karen’s uncle gave her an old Samsung model that he brought from Australia, which she used until the inconvenience of not having a matching charger for the phone compelled her to buy a new entry-level Alcatel smartphone for 149 kina (approximately US$50; Fig. 4).

For Karen, the phone was helpful in overcoming her nervousness about approaching her lecturers and tutors in person. She would instead call them and pay attention to how they conversed and asked her questions: “How may I help you?” Karen learned and repeated her lecturer’s conversational strategies in her face-to-face interactions with others, developing a sense of confidence and clarity in her public speaking. “I learned how to approach people…. I felt like my life changed.”

The phone allowed Karen to overcome her timidity (and she has witnessed similar transformations in other female university students). For example, Karen now has no hesitation about calling Digicel’s Customer Care when she has questions about the accuracy with which her prepaid balance of airtime is being managed. Dial 123, send: “How may I help you?” Digicel will find the right person to attend to her concern. The next time Karen makes a call, she will be charged at a lower rate. She is not sure how it works exactly. But they respond. “They respond…because I am their customer.” As a customer, Karen received the sort of recognition that many Papua New Guineans seek in vain from a state that has failed since independence in 1975 to bring development to its citizens in the form of tangible goods and services.

❧

Not all Digicel customers agree with Karen. The evidence is found on the Facebook page of the Digicel Complaints Group, a public forum for more than 43,000 mobile phone users. Group members who purchase airtime from Digicel, the dominant mobile network operator, use the forum to register dissatisfaction with the company’s services. They express particular concern about the conversion of prepaid airtime into data and the dubious ways in which Digicel adds and subtracts data from an individual’s balance. Complaints often concern the failure of credits to appear on a person’s phone after a purchase has been made or the disappearance of data from a person’s balance even when the phone is not in use.

My friend Cletus’s complaint to the group is fairly typical:

At exactly 11am today, I entered two K5 flex numbers: 01 7249 490 5910 & 16 2662 659 3637. At exactly 11:14am, Digicel sent me two messages: 1. Advised that I have used up my data and 2. Asked whether I need airtime of K13 advance. I immediately checked my balance only to see K5.03. I texted Digicel and 5 minutes [later] I was reimbursed K3 and not the whole K4.77. What a daylight robbery!

People sometimes post screenshots of the balances on their phones as evidence of stolen data. Accusations of robbery and theft, of being “ripped” (off), are commonplace. Such complaints recall historian E. P. Thompson’s (1971) well-known account of the protests that erupted as a moral economy of food provision gave way to practices and principles associated with “free trade” in 18th-century England. These protests, which often led to direct action, invoked notions of fair and transparent dealing in the face of concerns that the poor suffered at the hands of those with “command of a prime necessity of life” (Thompson 1971:93). Much like the folks about whom Thompson wrote, Digicel Complaints Group members express intense feelings over “weights and measures” and beseech the authorities to regulate business transactions. In other words, offended consumers look for help from the same neglectful state that let them down before Digicel arrived.

❧

The capacity of poor people to own and operate a phone in the developing world hinges on technologies of prepay, which allow users to pay as they go by buying small amounts of airtime when necessary or when funds become irregularly available. Managing one’s airtime requires tempering the practice of self-discipline with responsiveness to the obligations of caring for others.

Winnie is a heavy user who can spend up to 100 kina (US$33) a week in airtime credits. She is a young single woman living far from home and regards frequent communication with her family and friends as nothing less than essential. Winnie has a steady income and is generous when her kin send credit requests for airtime, which she can transfer directly to their phones for a small fee. She says that she is capable of spending all her savings on airtime, and she has on occasion come close to doing so by “topping up” her phone through a mobile banking account, a relatively new service that effectively enables users to purchase airtime anytime, anywhere. (A fair comparison is with gambling machines that provide access to a player’s bank account without requiring the player to leave his or her seat in front of the machine.) To discipline herself—and she used the English word discipline—Winnie has opened an account with another bank into which she makes weekly deposits. This bank, Winnie explained, does not offer the mobile top-up service. She has thus safeguarded her money from herself (see Foster, in press).

Winnie is explicit about the calculations that she makes in managing her mobile phone. She says that she does not feel able to start the day unless she is equipped to communicate. So, in the morning she will top up her phone for 5 kina (US$1.66). This top-up gives her 100 free promotional minutes for use between 11pm that night and 7am the following morning. She then purchases a one-day data pass: 60 MB for 3 kina. This data is enough to allow her to go online and communicate with friends and family via the applications WhatsApp and Viber. Winnie discovered that she could send voice messages over the internet for much less money than making voice calls. Finally, Winnie purchases a discounted bundle of 60 text messages for 1.20 kina. She will use most if not all of these text messages before they expire at midnight. That leaves 80 toea as a balance in case Winnie needs to make a quick phone call during the day (100 toea = 1 kina). (On-net calls from one Digicel phone to another are billed at 79 toea per minute, with per-second billing, during the peak hours of 7am to 9pm.) Once she has made these preparations, Winnie feels ready to go out into the world and meet the demands of the day.

❧

Winnie’s daily routine might understandably lead one to conclude that a peculiar kind of calculative rationality has been baked into the phone itself, such that Winnie’s habit of giving gifts to her relatives is subsumed within the sort of measuring and monitoring associated with markets and commodity exchange. This same tension between alternative logics of gift and commodity shapes the larger social and material assemblage of which the phone itself is part. It is a tension that threatens the future of customer care.

Matthew, a single man in his early thirties, repairs mobile phones and sells airtime at a street stand in the highlands town of Goroka (Fig. 5). He occupies a particular spot on a particular corner with other vendors who sell cigarettes, betel nuts, hard-boiled eggs, soft drinks, and the scratch (or “flex”) cards that people buy to top up their mobile phone airtime balances (Fig. 6). Matthew was one of the first to teach himself how to repair phones; he and his friend and workmate Gabriel were also among the first to start selling airtime in 2009 as Digicel expanded its network of cell towers across the country.

Matthew regards his work as a service to the community; indeed, to the nation. His business yields to the demands of a moral economy that Thompson would easily recognize. Villagers who come to town with no money can offer their homegrown bananas or sweet potatoes in exchange for repair services. Town workers, however, will be sized up and charged according to Matthew’s estimate of their ability to pay. The vendors, moreover, care for each other: they all offer their goods at the same price and eschew overt competition. One vendor’s business crashed when he overspent his revenue and was unable to purchase a new supply of scratch cards. A fellow vendor hired him until he was able, a year later, to save enough money to re-establish his own business.

Matthew insists that he and his fellow vendors are part of Digicel: without them the network would not work. His recognition of people as infrastructure is entirely plausible; Digicel still relies on vendors in places like Goroka to distribute airtime credit into the hinterlands where people prefer to buy scratch cards in town for use (or resale) later in the village. In cities like Port Moresby, however, the advent of smartphones has enabled more and more people to top up directly online, buying airtime like Winnie through linked banking accounts. Moreover, new forms of “self-care”—quite different from the kind of care that Matthew affords his customer—are being promoted. In January 2017, Digicel launched the My Digicel App for smartphone users, promising customers an efficient tool for “managing their Digicel life” (The National 2017). Several months later, the company introduced a menu that would allow customers, including users of basic handsets, to assist themselves with queries relating to data and top up, among other things. Dial *123#. 24/7. Free. A list of frequently asked questions appears on the phone’s screen.

The future of the prepaid scratch card is dubious, and the economic niche of street vendors is shrinking. There is a policy argument to be made that preservation of the scratch card vendors’ livelihood would support the so-called informal economy on which so many Papua New Guineans depend. For Matthew, however, it is an ethical as well as economic question: Does Digicel really care about him and his fellow vendors, who were present at the beginning when the company was first establishing itself in the country? His concerns echo those of the Digicel Complaints Group, and pose the unsettling question of whether Digicel still cares for the people of PNG 10 years after the company brought them a revolution in communications.

❧

Digicel of course expresses care and concern in ways that are familiar to corporate observers, if not immediately relevant to Matthew. The company has set up a branch of the Digicel Foundation in PNG as a way of giving back to the community by funding health and education projects—providing bits of infrastructure that the state has not—like a reliable nationwide telecommunications system. The company has even addressed one of the main problems for individuals in operating a mobile phone, namely keeping the battery charged. Outside of urban centers, which experience frequent power outages, access to electricity is severely restricted. Digicel has responded by marketing small solar panels for 95 kina (US$31; Fig. 7).

The Digicel Foundation attracts the standard critiques of corporate social responsibility: it’s window dressing and public relations and so on. Whether the Digicel Foundation is successful in promoting goodwill and positive sentiments among the people of PNG is unclear. The uptake of mobile phones in the country, however, continually surprises with respect to the capacity of these devices as affective technologies. My final ethnographic example underscores the high stakes involved in the emergence of a desirable new form of affective technology over which one’s control is exceedingly tenuous.

Lucy is in her early fifties, a rural woman with little education who, after being diagnosed as HIV positive, was struggling to live on her own after her older brother had refused to take her in.[1] A previous husband offered Lucy some money and a used mobile phone. Desperate, hungry, and contemplating suicide, Lucy began calling the contacts saved in the phone until one woman, instead of yelling and hanging up, agreed to speak with her. This woman, Angela, responded with compassion and began sending Lucy small gifts of food, money, and secondhand clothes. Lucy and Angela never met, but continued to talk by phone, thereby restoring Lucy’s feelings of hope and alleviating the anxieties that Lucy thought would reduce the effectiveness of her anti-retroviral medications. A friend found by chance on a random call enabled Lucy’s old mobile phone to function therapeutically as an affective technology, a medium for giving and receiving care.

Lucy’s story, like Matthew’s, exposes not only the possibilities but also the vulnerabilities inherent in the shifting moral economy of mobile phones. But Lucy’s story does not end well. Her phone, the source of Lucy’s emotional sustenance, was eventually stolen: “All those phone friends, in Port Moresby, Mt. Hagen, and other places, they would send me credit, and we talked all the time, every night, and now I don’t have a phone, and I’ve lost all those numbers. It’s terrible. I can’t stop crying about it. I had the same phone for four years, and had so many numbers, so many friends. And now it’s all gone.”