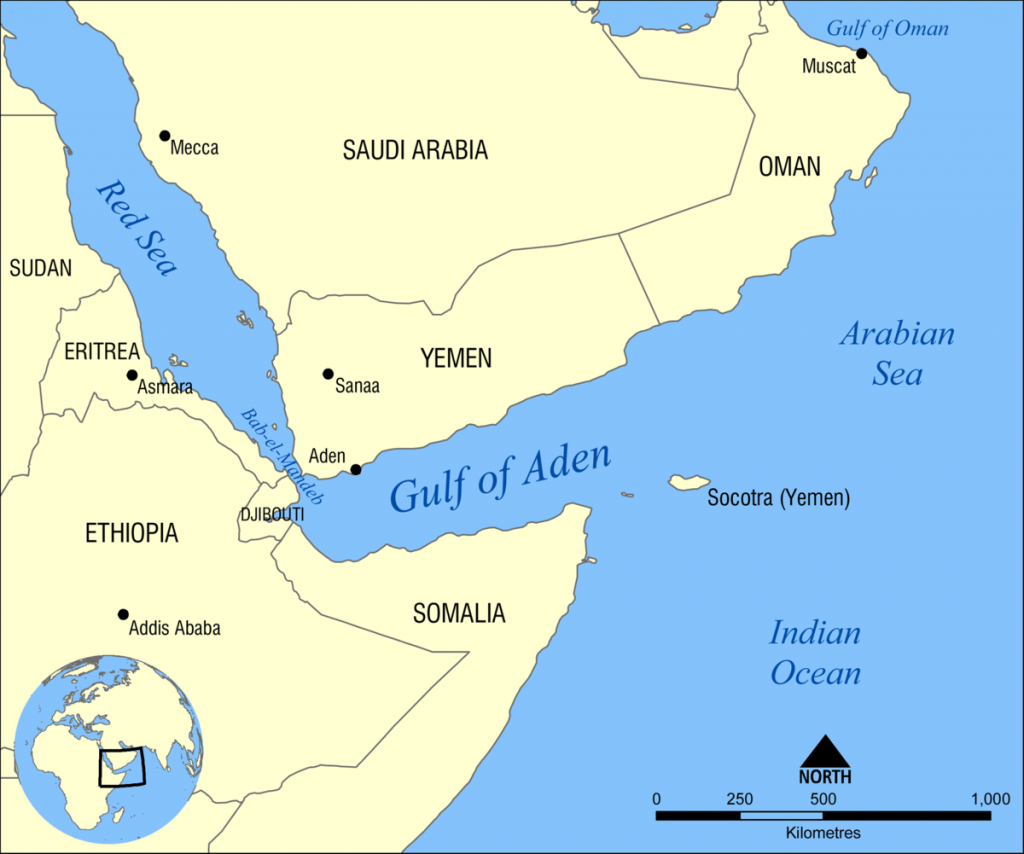

At the strategic intersection of the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, occupying the northern “door” of the Bab-el-Mandeb, the tiny nation-state of Djibouti hosts one of the largest ports in Africa and numerous military bases from countries as diverse as France, the United States, China, and Saudi Arabia. This mix of trade and security exemplifies a central aspect of what I call chokepoint sovereignty. Sovereignty as a “tentative and always emergent form of authority grounded in violence” (Hansen and Stepputat 2006) has, since Foucault, been tied to political claims over populations or territories that may or may not correspond to the framework of states. In contrast, chokepoint sovereignty is a form of authority that emerges from the power to channel and re-channel various kinds of global circulations. Instead of territory or population, Djibouti’s sovereignty rests on transforming its privileged location into an infrastructural and security hub—transforming the strait into a chokepoint.

This work of channeling and rechanneling is a process dependent as much on branding and regulation as on any inherent location. This is a world of glossy marketing brochures about vessel turnaround times and technologically advanced container terminals. This is a space constituted through the protection of lurking naval vessels and an Indian Ocean-wide surveillance network. It’s a place of mundane arrivals of those seeking refuge and return. Finally, chokepoint sovereignty is fragile. Built often on the rubble of historical attempts to transform location into resource, contemporary chokepoints are constantly threatened by rival claims of channeling.

Inside the Chokepoint

“Zone interdite!” (restricted zone). A uniformed port security officer had suddenly appeared in front of our car. “Zone interdite,” he repeated, this time holding his hand up and gesturing for us to stop. We had been snaking our way through the Port of Djibouti on a hot day in June 2016 with the marketing manager of the port. Earlier, at his office, the manager had thrust in my hand a shiny pamphlet that noted the locational advantage of the port as the gateway to Asia and Africa, and listed the steady increase in tonnage and number of vessels that used Djibouti as a port of call. After visiting the special area reserved for the shipment of goods to and from Ethiopia, we were heading towards the container terminal when the security officer suddenly halted our tour.

“We have a boat from Yemen,” the officer explained. Waiting behind an ambulance and two police vehicles, I watched a buzz of activity fill this otherwise quiet corner of the port. A Yemeni family had just arrived in a small car-ferry repurposed to transport a family of six and all sorts of household items, from fans to kitchen appliances, across the Bab-el-Mandeb, the narrow strait located between the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa. “Those who have some money or family,” the manager explained, “they come straight to the port of Djibouti, they get processed here and then rent a house. The ones without contacts or money they go to Obock and stay in tents in the middle of the desert,” referring to the small port town situated on the northern shore of the Gulf of Tajoura.

After a few minutes, as the port police and immigration officials filled out some paperwork, the family made their way into the waiting ambulance and headed away. As we drove past the car-ferry and its assorted cargo, I noticed it was docked next to a Yemeni coastguard boat. “These boats arrived from Aden in July [2015] when the Houthi forces took over,” the manager explained as we sped past, continuing our tour. “The Saudis and UAE have a base here now from where they support the Yemeni forces trying to take back Aden.

“Next stop, Doraleh container terminal—it’s the most technologically advanced container terminal on the African continent,” he remarked with no small hint of pride.

Chokepoint Histories

If these portside arrivals and the glimmering cranes of the Doraleh terminal illustrate the mix of violence and trade that constitute contemporary chokepoints, an old ramshackle building on the wide Boulevard de la Republique, which runs parallel to the coast in Djibouti city, is the place to understand the long histories of chokepoint sovereignty. A faded sign says “La Gare” indicating this was the terminus of the Chemin de Fer Franco-Éthiopien (CFE), the nineteenth-century, French-built railway line connecting Addis Ababa to the Red Sea. Depending on who’s around, it is possible to get a peek inside and walk amid the old ticket counters and waiting rooms before emerging on the platform. Here, you see the old narrow-gauge railway cars, rusting heaps of iron standing ghostlike on the tracks.

The French were relative latecomers when they arrived on the shores of northern Somaliland in order to exert influence over the Red Sea. From 1883 to 1887, French emissaries established a presence on the coast by signing a series of treaties with local Somali and Afar groups. Central to French ambitions in Somalia was the establishment of a railway line that connected Addis Ababa to the coast. In the early decades of the twentieth century, France invested heavily in the construction of the CFE and in developing the port facilities in Djibouti. However, unlike other colonial infrastructural projects throughout the continent, the bulk of the CFE ran through the ostensibly independent Ethiopian Empire creating a precarious position of imposing infrastructural control without political control. The railway line emerged as a mechanism of exploiting Ethiopia as a colony without assuming any of the responsibilities of colonialism. The railway line overlaid the old caravan paths that traversed the hinterland and the coast. From the 10th century onwards, the caravan trade was central to commercial and social life in the region. The establishment of the CFE railway sought to interrupt this flow through re-channeling these goods onto train carriages.

Today, another rechanneling is underway. As we stood under the crumbling awning, my guide remarked that “the Chinese are building a new railway, and they’ve built a new station near the airport.” In October 2016, with much fanfare, the Chinese-built Addis-Djibouti train service began functioning on a trial basis. Once completed, electric trains will connect passengers and cargo from land-locked Ethiopia to the newly built station near Djibouti City’s airport. From here, cargo will continue on diesel trains to the Doraleh terminal and onto waiting ships.

The inauguration of the railway line soon was followed by news of the opening of a Chinese naval base—the first overseas military base of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN)—adjacent to port. In combining trains and navy ships, the Chinese were continuing the nineteenth-century French model of combining trade and raid. In addition, the Chinese rhetoric of non-interference mirrors the French attempt at extraction without the responsibilities of colonialism.

These temporal echoes are central to the story of chokepoint sovereignty. Consider the rise of Djibouti Port, a process of port-making that emerged during the building of the CFE. The railway line sought to re-channel trade, often through force, away from the caravan route onto lumbering locomotives and—through this—shifting the coastal locus from Zeila (which was under British control) in the south and Obock in the north to the port of Djibouti. In the early twentieth century, the port of Djibouti emerged from a small ramshackle set of settlements into one of the most significant ports in the region, acting as a bottleneck for the mobility of goods and people across the Red Sea.

Through these projects of re-channeling thus was created a chokepoint—a bottleneck place—of slowdown and then speeding up. This mode of re-channeling also entailed a transformation of regulatory authority. Lighthouses, military and naval patrols, the use of ship identification papers, and various decrees that regularized the flows of ship traffic—including the establishment of quarantines near the Djibouti port—all were central in the emergence of Djibouti as port, as military base, as colony, and eventually as sovereign state.

Port-making as State-making

The intertwining of state-making and port-making—of commerce and violence that began with the CFE—continued with the transition to Djibouti independence in 1977. Alongside the port, military bases emerged. Initially these were French, but in a post-9/11 and post-Somali piracy world the United States, the European Union, China, and Japan have become the main sources of revenue and the raison d’état of Djibouti. All these projects have foregrounded the country’s location on the Bab-el-Mandeb as central to the building of this trade and security infrastructure.

This emphasis on location was repeated numerous times while I was doing research in Djiobuti in 2016. That summer, in the small bustling office of the Djibouti Ports Authority, an energetic team of young marketing graduates was hard at work. “We’re branding the port as the crossroads of Asia and Africa,” explained Fatima, the chief of marketing for the port and the one responsible for producing the glossy brochures I had been given. Over the next few weeks, I observed Fatima and her team sell berthing space at the port to clients from around the world in addition to arranging tours of the port for a variety of visitors.

“Location is what makes Djibouti,” she said. “We’re a small piece of land otherwise. It helps us that we’re surrounded by war on all sides.” She smiled as she uttered the last sentence. Then, perhaps recognizing that she might be coming across as a bit callous, she clarified, “I mean, strictly from a business sense. War is obviously not something to wish on one’s neighbors, but it’s good for business!”

In Djibouti, location transforms into a form of sovereign branding. With respect to the Djibouti port, it is the promise of a regulated space legible within a world of international standards and technologies. As the port manager in Djibouti explained in 2015, “What you get when you choose Djibouti is both access to Ethiopia and East Africa but also a port that has all the standards of a global port. In fact, we are launching a green initiative and plan to be one of Africa’s first green ports.”

This aspect of branding also was central when the port of Djibouti created a partnership with Dubai Port World. Inaugurated with much fanfare in 2000, the partnership between Djibouti and the Dubai-based DP World was meant to solidify Djibouti’s claim as the main port of call on the Bab-el-Mandeb, eclipsing Aden across the Strait. In addition to establishing a container terminal in Doraleh adjacent to the old Djibouti Port, DP World also constructed a dry port and special economic zone modeled after the Jebel Ali Free Zone in Dubai. DP World was a signifier of regulatory stability, a transnational guarantor of chokepoint sovereignty.

Ambiguity of Location

Location, though, is a fickle friend. Ports wax and wane, appear and disappear. New bottlenecks form, along with new possibilities of profits and power. In the summer of 2016, Djibouti woke to this possibility.

By 2014, shipping and transportation accounted for one third of Djibouti’s GDP, and the container port in Doraleh was scheduled to process more than 3 million containers per year. In the midst of this revenue boom, the government of Djiobuti canceled the contract with DP World and began arbitration proceedings against it in the United Kingdom. In 2016, DP World negotiated a deal in Berbera, Somaliland, to develop a “new Djibouti” on the Red Sea. Berbera’s closer proximity to Ethiopia always was acknowledged by port officials in Djibouti as a potential impediment to Djibouti’s hegemony over the Ethiopia trade. DP World’s investment plans were viewed as a direct attack on Djibouti, an attempt at unmaking its chokepoint sovereignty through re-channeling trade further south on the Red Sea. In another setback to Djibouti, Britain’s High Court dismissed the arbitration case in early 2016.

But an unlikely ally for Djibouti emerged when the new president of Somalia, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed Farmaajo, during his first official state visit to Saudi Arabia in February 2017 stated that he would seek Saudi intervention against the UAE’s plans to open a military and counter-piracy base in Somaliland as well as DP World’s port-expansion plans. Citing Somaliland’s non-recognition of sovereignty, Farmaajo’s regime has challenged Somaliland’s ability to make contracts, a power that legally falls under the purview of the central government in Mogadishu. In these dramas of recognition, ports become sites to articulate and litigate the spectral and real figures of sovereignty, and the coming battle between Djibouti, Berbera, and Mogadishu will seek to redraw the maps of mobility—of goods, people, and capital that determine the rhythms of life around the chokepoint.

Chokepoint sovereignty emphasizes the dynamic ways in which the ability to channel and re-channel is central in claiming political authority and profits from practices of global mobility. Built on the debris of longer histories, this process, as the case of Djibouti highlights, interweaves trade, violence, and regulation, thus transforming location into spaces of possibility and encounter.