Calais’ Invisible Jungle

On October 25, 2016, French riot police evicted thousands of migrants who had settled in an abandoned landfill adjacent to the port of Calais. They were gathered there hoping to cross the English Channel by any means necessary: stowing away on boats or hiding in the trains, trucks, and buses plying the “Chunnel” linking France to Britain. Hundreds of makeshift houses and tents of

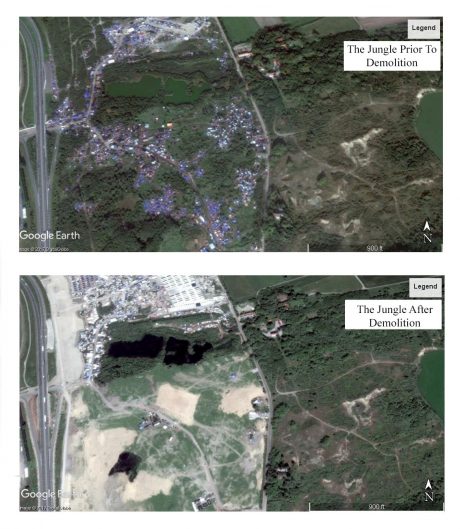

Satellite view of the Calais Jungle, Google Earth, accessed December 29, 2017 Google Earth

the so-called “Calais Jungle” were bulldozed or burned while the police forced migrants to board buses taking them to asylum centers scattered through the French countryside.

Paradoxically, the effort to wipe the camp off the map thrust the Jungle to the fore of international attention. In time, the demolition came to be seen as emblematic of the “European migration crisis” writ large. Yet this was hardly the first effort to control—and render invisible—the persistent rush of humanity seeking illicit passage through the Chunnel. Since the 1990s, migrant communities gathered in and around Calais have been met with a steadily evolving array of infrastructure, technologies, and security apparatuses. These anti-intrusion measures, however, have not prevented migrants from coming to Calais in hopes of rebuilding their lives in the United Kingdom. Indeed, by 2017, migrants were back in Calais and facing increasingly violent treatment, with police reportedly pouring tear gas into potable water sources to render the area uninhabitable (Beatrice D 2017).

A Counter-Optics

This photo essay explores these attempts to control migration and the persistence of migrant encampments in the face of them. Countering the technologies of invisibility deployed to remove migrants from Calais, we combine word and image to expose—and render visible—the infrastructural forms and lifeforms that converge at this critical chokepoint. The tensions arising between these representations, we hope, may lead to more humanized ends than the demolitions of 2016.

The Makings of a Chokepoint

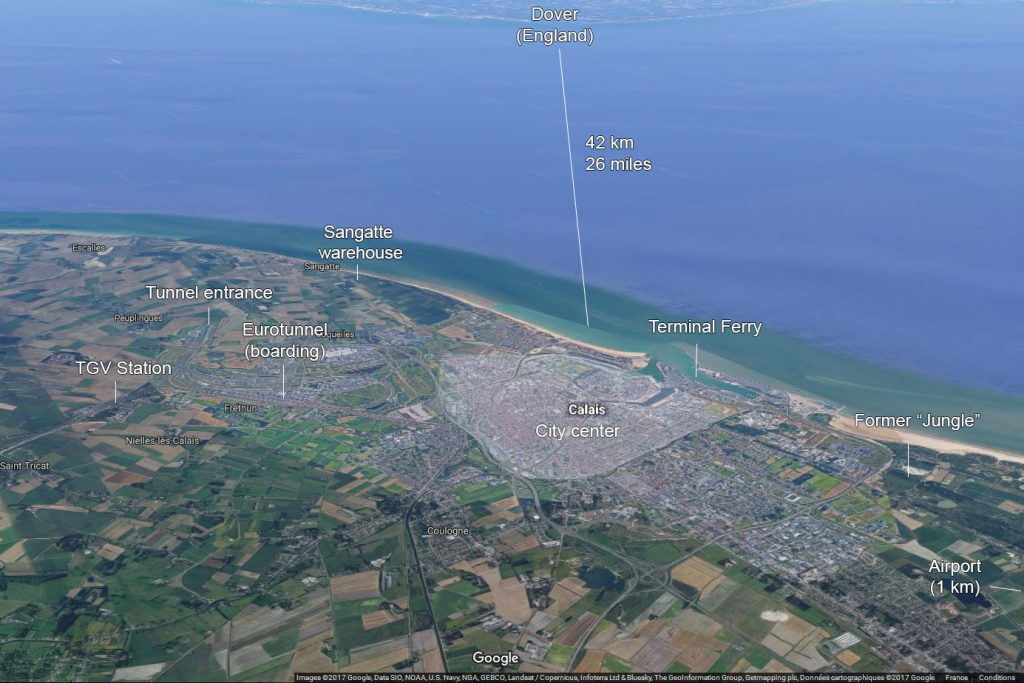

On November 14, 1994, Eurostar high-speed trains started to link Paris and Brussels to London using the tunnel dug beneath the Strait of Dover. It took six years, eleven boring machines, and more than 15,000 workers to link Calais, France, and Folkestone, England.

Every year, approximately 10 million people cross the 23.5-mile “Chunnel.” Almost 1.6 million trucks are carried through the Chunnel’s rail-transport shuttle alone. The ferry traffic is even more intense: an estimated 4 million trucks and 14 million passengers cross the Strait of Dover by sea every year, making the English Channel the most congested maritime route in the world (Shurmer-Smith and Turbout 2017; Mambra 2017).

From Chunnel to “Jungle”

As the number of migrants in Calais escalated, the French government in 1999 asked the French Red Cross to open a transit center in a warehouse in Sangatte, a small countryside town. At its peak activity, the center sheltered more than 1,500 people (Kremer 2002). Countless more eventually gathered outside these formal infrastructures, waiting for their opportunity to slip undetected through the chokepoint to Britain.

In/Visible Life

Over the past fifteen years, security infrastructure and police presence have been the main responses to these attempted crossings. The French and British authorities placed cameras at the entrance of the tunnel, surrounded the port with fences, and ramped up X-ray searches of trucks. The French government reinforced police presence by sending the Gendarmerie Mobile and the notoriously brutal Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité—France’s riot police, the majority of whom support the extreme right party Front National and have a long history of racial profiling and violence (Piccolo and Debuis 2017; Childers 2016: 116). Since going to Sangatte often would mean being denied asylum by France and being deported, migrants had no choices but to hide and live in the woods of the northern French coast while waiting for a chance to cross the channel.

The Suction Theory

In 2002, then-Minister of Interior Affairs Nicolas Sarkozy ordered the closing of the Sangatte center after it sheltered more than 70,000 people in three years. The humanitarian camp, according to Sarkozy, created a suction effect—“un appel d’air”—and supposedly increased clandestine immigration in France. Now ubiquitous in French politics, the “suction theory” has translated into ever-increasing police brutality against migrants and expansion of security infrastructure.

Since 1999, the French government repeatedly has opened shelters and day camps away from Calais, cutting off migrants from the solidarity networks that long have existed in this city. As activists of Calais Migrant Solidarity put it, “What we are witnessing is the creation of a racial ghetto under the guise of liberal humanitarian concern” (CMS 2015). Migrants’ allies are seldom allowed to visit the camp, while people sheltered there are warned that venturing back to Calais would mean certain starvation and state-mandated violence. With the recurrent opening and closing of these official camps, multiple “jungles” have continually appeared in and around Calais.

French police have tracked and brutalized migrants camping in the woods or “jungles.” In the meantime, legal authorities have sentenced activists and drastically reduced the margins of action for humanitarian NGOs and local organizations. In 2009, the right-wing Interior Ministry ordered the bulldozing of the Calais Jungle while a thousand migrants lived there. The camp soon was rebuilt. The recent migration surge towards Europe led France’s Interior Ministry to order the 2016 bulldozing. An estimated 6,000 migrants lived there at the time. Since then, the rhetoric only has escalated. In 2017, center-left-wing Interior Minister, Gérard Collomb, sustained the call for the eradication of jungles, which he depicted as places where “encysted migrants” lived in “fixation abscesses” that need to be “treated” (Mouillard 2017). Pathologizing migration, Collomb also offered a medieval solution: bursting the abscess by accruing police presence and scattering migrants in new camps that will open in the countryside (AFP 2017).

Preventative Infrastructures

The borders and jurisdictions around Calais are blurry. In 2003, for instance, British border control officers gained the right to perform checks in Brussels and Calais. Moreover, in 2016, the British authorities financed and constructed a 30 million-dollar anti-intrusion barrier that runs a kilometer along the entrance road to the Calais port. Cosmeticized with vegetation, the “Great Wall of Calais” is made of smooth concrete to impede climbing.

Groupe Eurotunnel SE, meanwhile, deforested more than a thousand square feet of land around the Chunnel entrance and flooded the entire area to prevent migrants from entering the tunnel. This intervention into infrastructure meant to reverse the migration “suction effect”—that is, to scatter migrants away from the chokepoint—stands in telling contrast to the ever-increasing legal flows of goods and people crossing the strait on state-of-the-art transportation devices. In their stark materiality, preventative infrastructures such as the wall and the flooding draw sharp lines between the licit and illicit movements—and lives—that animate this chokepoint.

Toward Other Ends

Rendering migration invisible through repression, security infrastructure and the establishment of camps doesn’t mask the need for new immigration politics in Europe. If intensifying traffic between Britain and France was thought as a logistical issue in the 1980s, the human dynamics of the Calais chokepoint are an integral part of the lawful and unlawful traffic between Britain and continental Europe. “Jungles,” solidarity networks between locals and migrants, interactions between state actors, businesses, and other stakeholders do not simply shape mobility; they transform chokepoint space into inhabited places, both vital and vulnerable. These converging forces imbue chokepoint life with a resiliency that cannot be regulated through violence and forced displacement. A counter-optics that renders chokepoint lives visible may accordingly point the way to different means for managing life and movement at these critical passageways.

Envisioning more humane means and ends, it’s clear there is no need for a wall if migration policy is built around the humanity and political agency of migrants. Offering them a clear path to equal citizenship and the power to decide where they can live and work would be a way for the European Union to regain some dignity after its catastrophic mismanagement of the migration surge at its Mediterranean borders. To rethink migration in this way would be to draw a new line of policy—a new line of humanity—linking chokepoints in Libya, Turkey, Sicily, Calais, and beyond. It is to imagine a world without ‘jungles’ and their attended forms of invisibility.