[ Ed. note: This is the first of a three part collaboration on “Excrementa Estates.” Read parts II and III. ]

The Introduction

Combining architectural models and drawings, graphic texts, and photographs, the following section is an exercise in critical design anthropology, serving a dual purpose of documentation and provocation. Building on African solutions to African problems—namely the shortage of urban sanitary facilities—Excrementa Estates promotes innovative multi-use dwelling design. Four design models are featured: Stomach Has No Holiday, Adepa, Lady Di, and Doctor. Each combines private residential space with toilets and baths available to the wider public on a fee-for-service basis. In development parlance, these can be glossed as dwelling-based public toilets (DBPTs).

All of the designs draw from Ghana’s edge-city of Ashaiman. Located near Ghana’s port of Tema and national capital, Accra, Ashaiman is a fast-growing urban settlement largely occupied by working-class migrants and transients with access to no or low-quality dwellings. The city has no central sewage system and limited municipal facilities. Nevertheless, due to the low price of land and proximity to Ghana’s commercial core, Ashaiman is also home to an upwardly mobile social stratum. With space, capital, and status to spare, many well-off households invest in excrement-based enterprise, tapping the bodily needs and pocketbooks of less prosperous neighbors. Variations on a theme, the four models highlighted here afford different opportunities for privacy, propriety, and enterprise development and offer a range of for-profit sanitary solutions, from flush and squat toilets and showers and baths to tap, tank, and purified water; water closet; septic tank; and pit latrine. Each one is already in use in the city. All of the DBPTs showcased offer a distinctive synthesis of domestic space, public access, sanitary infrastructure, and commercial imperatives in a context of minimal state provisioning.

These popularly derived solutions to pressing urban and human needs are presented via customized real estate brochures, a promotional and informational modality common across the African continent. The brochures are juxtaposed with architectural drawings and three-dimensional models derived from the structures built and used by Ashaiman residents. This format provides a way to ponder the viability of corporatized mass production of vernacular problem solving. Mixing low and high, public service and for-profit urban sanitation solutions, and aestheticized abstraction and on-the-ground realities, Excrementa Estates uses the conditions of the present to imagine designs for the future in Africa’s fast-growing cities. Abstracted and miniaturized, these designs for living and the pan-human need for bodily care and evacuation raise questions about the source, scale, and replicability of “development devices.” Although the sanitary solutions found in Ashaiman can be packaged and promoted, their capacity for circulation and adaptation is open to debate.

THE MODELS

Stomach Has No Holiday is situated amid the shanties of Ashaiman’s working poor. With 16 toilets and 8 showers stalls, it is near but detached from the owner-operator’s family home among a cluster of other family-based enterprises. A source of retirement income and status recognition for the proprietor, Stomach represents a beacon of prosperity and service provision in an otherwise impoverished locale. Bucking the municipality’s efforts to control its operation or design, the low-tech, low-cost, yet well-maintained pit latrine offers affordability for the local populace and promises profits and permanence in a largely transient space.

Stomach Has No Holiday is situated amid the shanties of Ashaiman’s working poor. With 16 toilets and 8 showers stalls, it is near but detached from the owner-operator’s family home among a cluster of other family-based enterprises. A source of retirement income and status recognition for the proprietor, Stomach represents a beacon of prosperity and service provision in an otherwise impoverished locale. Bucking the municipality’s efforts to control its operation or design, the low-tech, low-cost, yet well-maintained pit latrine offers affordability for the local populace and promises profits and permanence in a largely transient space.

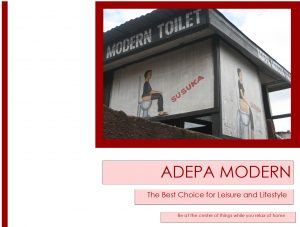

Adepa (a Twi term meaning “It’s nice”) is a compact enclosure containing eight top-of-the-line flush water closet (WC) toilets and porcelain hand sinks. Situated at the rear of the domicile, its separate entrance sets it apart from residential space, which is close enough for convenient monitoring and servicing yet affords privacy. Located in a long-settled neighborhood of large compound-style homes, Adepa is an attractive alternative to the overburdened and sensorially offensive municipal toilet. Despite the steep price of entry, Adepa is well patronized due to the high quality of service and good reputation of its proprietors. Toilet-related services and socializing extend into the public space and thoroughfares surrounding Adepa, all the while maintaining respect and discretion for customers.

Adepa (a Twi term meaning “It’s nice”) is a compact enclosure containing eight top-of-the-line flush water closet (WC) toilets and porcelain hand sinks. Situated at the rear of the domicile, its separate entrance sets it apart from residential space, which is close enough for convenient monitoring and servicing yet affords privacy. Located in a long-settled neighborhood of large compound-style homes, Adepa is an attractive alternative to the overburdened and sensorially offensive municipal toilet. Despite the steep price of entry, Adepa is well patronized due to the high quality of service and good reputation of its proprietors. Toilet-related services and socializing extend into the public space and thoroughfares surrounding Adepa, all the while maintaining respect and discretion for customers.

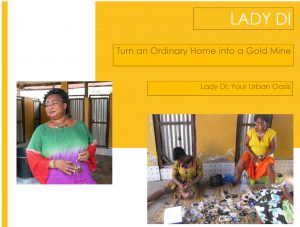

The Lady Di  DBPT is altogether different in design. Contiguous with the family living area, this 20-toilet and 12-bath complex is equivalent in size to the already spacious home to which it is connected. Combining the toilet and bath enterprise with a lucrative water business consisting of an on-site borehole, multiple storage tanks, and a dedicated filtration system, there is no clear boundary between dwelling space and commercial operations. As such, toilet customers and toilet cleaners are incorporated into household life. In turn, the businesswoman and her female offspring who run, own, and live within the facility gain wealth, regard, and a broad network of dependents by keeping waste-work at home.

DBPT is altogether different in design. Contiguous with the family living area, this 20-toilet and 12-bath complex is equivalent in size to the already spacious home to which it is connected. Combining the toilet and bath enterprise with a lucrative water business consisting of an on-site borehole, multiple storage tanks, and a dedicated filtration system, there is no clear boundary between dwelling space and commercial operations. As such, toilet customers and toilet cleaners are incorporated into household life. In turn, the businesswoman and her female offspring who run, own, and live within the facility gain wealth, regard, and a broad network of dependents by keeping waste-work at home.

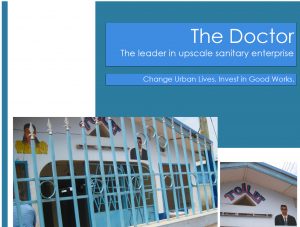

The Doctor depicts a DBPT owned and operated by a prominent physician. Located on an expansive lot in an up-and-coming neighborhood well beyond Ashaiman’s congested commercial core, the toilet occupies the entirety of a structure originally built to serve as a residence. Now converted to a toilet facility, with 14 men’s rooms on one side and 14 ladies’ rooms on the other, the only dwelling space that remains is the office area reserved for the attendants; the doctor-owner lives elsewhere. The attractive fence, decorated gate, airy veranda, and large lot provide cover for a multi-corridor shower area. Blending in with neighboring domestic structures, this large-scale facility is well prepared to handle urban infill.

depicts a DBPT owned and operated by a prominent physician. Located on an expansive lot in an up-and-coming neighborhood well beyond Ashaiman’s congested commercial core, the toilet occupies the entirety of a structure originally built to serve as a residence. Now converted to a toilet facility, with 14 men’s rooms on one side and 14 ladies’ rooms on the other, the only dwelling space that remains is the office area reserved for the attendants; the doctor-owner lives elsewhere. The attractive fence, decorated gate, airy veranda, and large lot provide cover for a multi-corridor shower area. Blending in with neighboring domestic structures, this large-scale facility is well prepared to handle urban infill.